Stan: Probabilistic Modeling and Bayesian Inference

Coding Club

January 2019

Summary

Stan is a probabilistic programming language for specifying statistical models. Stan provides full Bayesian inference for continuous-variable models through Markov chain Monte Carlo methods such as the No-U-Turn sampler, an adaptive form of Hamiltonian Monte Carlo sampling.

Penalized maximum likelihood estimates are calculated using optimization methods such as the limited memory Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno algorithm.

Stan can be called through R using the rstan package, and through Python using the pystan package. Both interfaces support sampling and optimization-based inference with diagnostics and posterior analysis.

In this talk it is shown a brief glance about the main properties of Stan. It is shown, also a couple of examples: the first one related with a simple Bernoulli model and the second one, about a Lotka-Volterra model based on ordinary differential equations.

What is Stan?

Stan is named in honor of Stanislaw Ulam (1909-1984): Co-inventor of the Monte Carlo method.

Stan is an imperative probabilistic programming language.

A Stan program defines a probability model.

It declares data and (constrained) parameter variables.

It defines log posterior (or penalized likelihood).

Stan inference: fits model to data and makes predictions.

It can use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) for full Bayesian inference.

Or Variational Bayesian (VB) for approximate Bayesian inference.

Or Maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) for penalized maximum likelihood estimation.

What does Stan compute?

Draws from posterior distributions

Stan performs Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling

Produces sequence of draws \[ \theta_{(1)} ,\theta_{(2)}, \ldots, \theta_{(M)} \]

where each draw \( \theta_{(i)} \) is marginally distributed according to the posterior \( p(\theta|y) \)

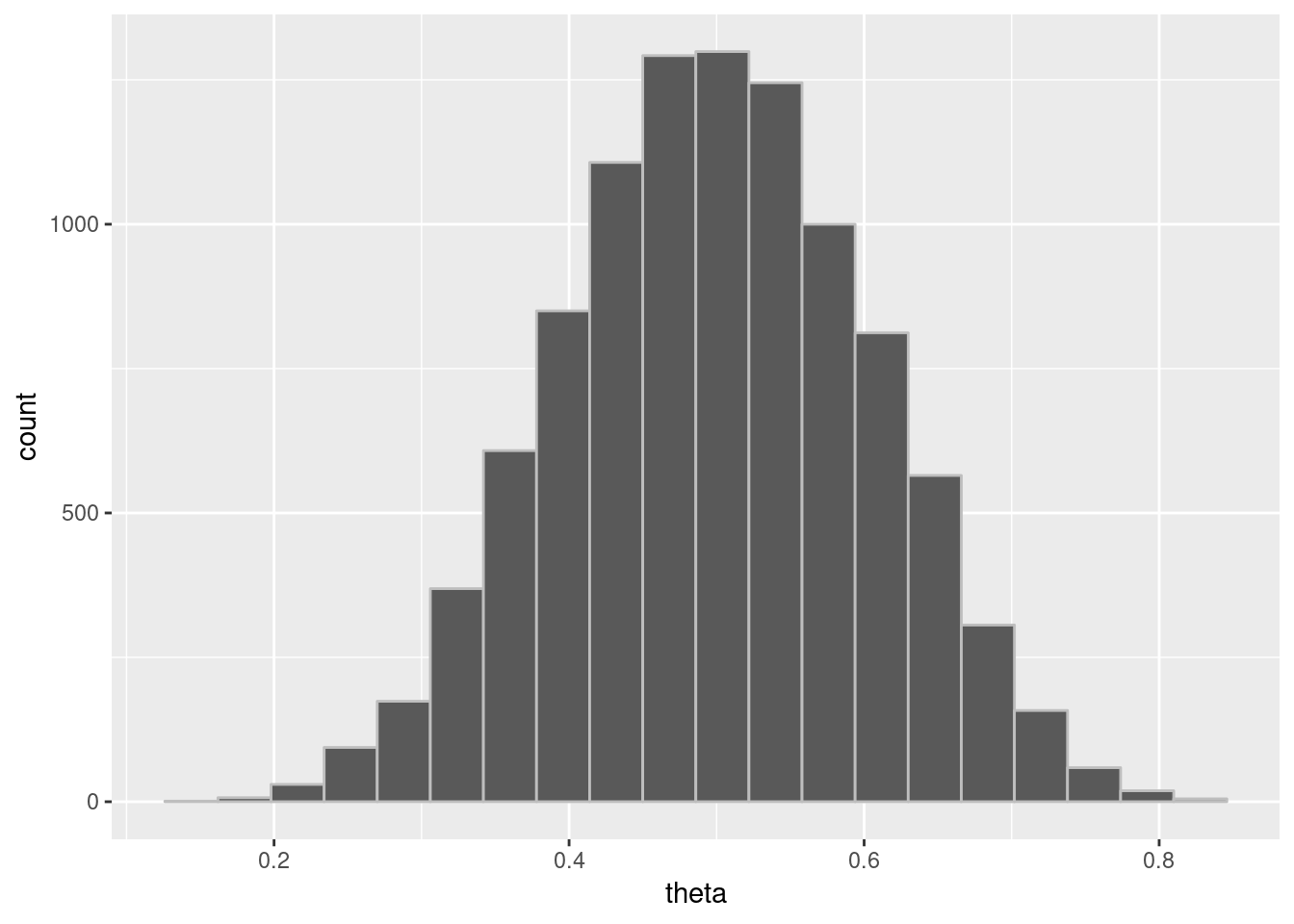

Draws characterize posterior distributions

Plot with histograms, kernel density estimates, etc.

-

https://github.com/stan-dev/rstan/wiki/RStan-Getting-Started

Installing rstan

There are several frameworks for Stan with R, Python, MatLab, etc:

https://mc-stan.org/users/interfaces/index.html

Before installing rstan in Windows it is necessary to install Rtools.

https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/Rtools

You have to check whether the path (in Windows) is correctly fixed for all binaries of Rtools.

If it is not the case, write in R:

install.packages(devtools)

library(devtools)

Sys.setenv(PATH = paste("C:\\Rtools\\bin", Sys.getenv("PATH"), sep=";"))

Sys.setenv(PATH = paste("C:\\Rtools\\mingw_64\\bin", Sys.getenv("PATH"), sep=";"))

install.packages(rstan)

Basic syntax in Stan

A Stan model is defined by five program blocks data

data (required)

transformed data

parameters (required)

transformed parameters

model (required)

generated quantities

- The data block reads external information

data {

int N;

int x[N];

int offset;

}

- The transformed data block allows for preprocessing of the data

transformed data {

int y[N];

for (n in 1:N)

y[n] = x[n] - offset;

}

- The parameters block defines the sampling space

parameters {

real<lower=0> lambda1;

real<lower=0> lambda2;

}

- The transformed parameters block allows for parameter processing before the posterior is computed

transformed parameters {

real<lower=0> lambda;

lambda = lambda1 + lambda2;

}

- In the model block we define our posterior distributions

model {

y ~ poisson(lambda);

lambda1 ~ cauchy(0, 2.5);

lambda2 ~ cauchy(0, 2.5);

}

- Lastly, the generated quantities block allows for postprocessing

generated quantities {

int x_predict;

x_predict = poisson_rng(lambda) + offset;

}

Stan has two primitive types and both can be bounded.

int is an integer type

real is a floating point precision type

int<lower=1> N;

real<upper=5> alpha;

real<lower=-1,upper=1> beta;

real gamma;

real<upper=gamma> zeta;

- Reals extend to linear algebra types

vector[10] a; // Column vector

matrix[10, 1] b;

row_vector[10] c; // Row vector

matrix[1, 10] d;

- Arrays of int, reals, vectors, and matrices are available

real a[10];

vector[10] b;

matrix[10, 10] c;

- Stan also implements a variety of constrained types

simplex[5] theta; // sum(theta) = 1

ordered[5] o; // o[1] < ... < o[5]

positive_ordered[5] p;

corr_matrix[5] C; // Symmetric and

cov_matrix[5] Sigma; // positive-definite

- All the tipical control and loop statements are available, too

if/then/else

for (i in 1:I)

while (i < I)

- There are two ways to modify the posterior

y ~ normal(0, 1);

target += normal_lpdf(y | 0, 1);

# Deprecated in new versions of Stan:

increment_log_posterior(log_normal(y, 0, 1));

- Many sampling statements are vectorized

parameters {

real mu[N];

real<lower=0> sigma[N];

}

model {

// for (n in 1:N)

// y[n] ~ normal(mu[n], sigma[n]);

y ~ normal(mu, sigma); // Vectorized version

}

Bayesian approach

Probability is Epistemic

For instance, John Stuart Mill (Logic 1882, Part III, Ch. 2) said:

… the probability of an event is not a quality of the event itself, but a mere name for the degree of ground which we, or some one else, have for expecting it. Every event is in itself certain, not probable; if we knew all, we should either know positively that it will happen, or positively that it will not. … its probability to us means the degree of expectation of its occurrence, which we are warranted in entertaining by our present evidence.

Probabilities quantify uncertainty

Statistical reasoning is counterfactual

Repeated Binary Trial Model

Data

- \( N\in \{0,1,\ldots \} \)

- \( y_{n}\in \{0,1\} \) trial n success (known, modeled data)

Parameter

- \( \theta \in \lbrack 0,1] \): chance of success (unknown)

Prior

- \( p(\theta) = Uniform(\theta|0,1) = 1 \)

Repeated Binary Trial Model

- Likelihood

\[ p(y|\theta )=\prod_{n=1}^{N}Bernoulli(y_{n}|\theta )=\prod_{n=1}^{N}\theta ^{y_{n}}(1-\theta )^{1-y_{n}} \]

- Posterior

\[ p(\theta |y)\propto p(\theta )p(y|\theta ) \]

Stan Program

bern.stan =

"

data {

int<lower=0> N; // number of trials

int<lower=0, upper=1> y[N]; // success on trial n

}

parameters {

real<lower=0, upper=1> theta; // chance of success

}

model {

theta ~ uniform(0, 1); // prior

y ~ bernoulli(theta); // likelihood

}

"

R: Simulate some data

# Generate data

theta = 0.30

N = 20

y = rbinom(N, 1, 0.3)

y

[1] 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0

- Calculate MLE as sample mean from data

sum(y) / N

[1] 0.3

RStan: Bayesian Posterior

library(rstan)

fit = stan(model_code=bern.stan, data = list(y = y, N = N), iter=5000)

SAMPLING FOR MODEL 'bfd58553d9dcc0c7cf662698c8aa5414' NOW (CHAIN 1).

Chain 1:

Chain 1: Gradient evaluation took 5e-06 seconds

Chain 1: 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.05 seconds.

Chain 1: Adjust your expectations accordingly!

Chain 1:

Chain 1:

Chain 1: Iteration: 1 / 5000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

Chain 1: Iteration: 500 / 5000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

Chain 1: Iteration: 1000 / 5000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

Chain 1: Iteration: 1500 / 5000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

Chain 1: Iteration: 2000 / 5000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

Chain 1: Iteration: 2500 / 5000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

Chain 1: Iteration: 2501 / 5000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

Chain 1: Iteration: 3000 / 5000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

Chain 1: Iteration: 3500 / 5000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

Chain 1: Iteration: 4000 / 5000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

Chain 1: Iteration: 4500 / 5000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

Chain 1: Iteration: 5000 / 5000 [100%] (Sampling)

Chain 1:

Chain 1: Elapsed Time: 0.014033 seconds (Warm-up)

Chain 1: 0.013641 seconds (Sampling)

Chain 1: 0.027674 seconds (Total)

Chain 1:

SAMPLING FOR MODEL 'bfd58553d9dcc0c7cf662698c8aa5414' NOW (CHAIN 2).

Chain 2:

Chain 2: Gradient evaluation took 3e-06 seconds

Chain 2: 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.03 seconds.

Chain 2: Adjust your expectations accordingly!

Chain 2:

Chain 2:

Chain 2: Iteration: 1 / 5000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

Chain 2: Iteration: 500 / 5000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

Chain 2: Iteration: 1000 / 5000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

Chain 2: Iteration: 1500 / 5000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

Chain 2: Iteration: 2000 / 5000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

Chain 2: Iteration: 2500 / 5000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

Chain 2: Iteration: 2501 / 5000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

Chain 2: Iteration: 3000 / 5000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

Chain 2: Iteration: 3500 / 5000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

Chain 2: Iteration: 4000 / 5000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

Chain 2: Iteration: 4500 / 5000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

Chain 2: Iteration: 5000 / 5000 [100%] (Sampling)

Chain 2:

Chain 2: Elapsed Time: 0.01328 seconds (Warm-up)

Chain 2: 0.013659 seconds (Sampling)

Chain 2: 0.026939 seconds (Total)

Chain 2:

SAMPLING FOR MODEL 'bfd58553d9dcc0c7cf662698c8aa5414' NOW (CHAIN 3).

Chain 3:

Chain 3: Gradient evaluation took 2e-06 seconds

Chain 3: 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.02 seconds.

Chain 3: Adjust your expectations accordingly!

Chain 3:

Chain 3:

Chain 3: Iteration: 1 / 5000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

Chain 3: Iteration: 500 / 5000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

Chain 3: Iteration: 1000 / 5000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

Chain 3: Iteration: 1500 / 5000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

Chain 3: Iteration: 2000 / 5000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

Chain 3: Iteration: 2500 / 5000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

Chain 3: Iteration: 2501 / 5000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

Chain 3: Iteration: 3000 / 5000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

Chain 3: Iteration: 3500 / 5000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

Chain 3: Iteration: 4000 / 5000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

Chain 3: Iteration: 4500 / 5000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

Chain 3: Iteration: 5000 / 5000 [100%] (Sampling)

Chain 3:

Chain 3: Elapsed Time: 0.013933 seconds (Warm-up)

Chain 3: 0.01306 seconds (Sampling)

Chain 3: 0.026993 seconds (Total)

Chain 3:

SAMPLING FOR MODEL 'bfd58553d9dcc0c7cf662698c8aa5414' NOW (CHAIN 4).

Chain 4:

Chain 4: Gradient evaluation took 2e-06 seconds

Chain 4: 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.02 seconds.

Chain 4: Adjust your expectations accordingly!

Chain 4:

Chain 4:

Chain 4: Iteration: 1 / 5000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

Chain 4: Iteration: 500 / 5000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

Chain 4: Iteration: 1000 / 5000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

Chain 4: Iteration: 1500 / 5000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

Chain 4: Iteration: 2000 / 5000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

Chain 4: Iteration: 2500 / 5000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

Chain 4: Iteration: 2501 / 5000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

Chain 4: Iteration: 3000 / 5000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

Chain 4: Iteration: 3500 / 5000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

Chain 4: Iteration: 4000 / 5000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

Chain 4: Iteration: 4500 / 5000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

Chain 4: Iteration: 5000 / 5000 [100%] (Sampling)

Chain 4:

Chain 4: Elapsed Time: 0.013922 seconds (Warm-up)

Chain 4: 0.013241 seconds (Sampling)

Chain 4: 0.027163 seconds (Total)

Chain 4:

print(fit, probs=c(0.1, 0.9))

Inference for Stan model: bfd58553d9dcc0c7cf662698c8aa5414.

4 chains, each with iter=5000; warmup=2500; thin=1;

post-warmup draws per chain=2500, total post-warmup draws=10000.

mean se_mean sd 10% 90% n_eff Rhat

theta 0.32 0.00 0.10 0.20 0.45 3564 1

lp__ -14.29 0.01 0.76 -15.16 -13.77 4475 1

Samples were drawn using NUTS(diag_e) at Fri Jan 25 17:33:51 2019.

For each parameter, n_eff is a crude measure of effective sample size,

and Rhat is the potential scale reduction factor on split chains (at

convergence, Rhat=1).

- We obtain something similar to

Inference for Stan model: a6e9032b5e2c0ad2011961902392006a.

4 chains, each with iter=5000; warmup=2500; thin=1;

post-warmup draws per chain=2500, total post-warmup draws=10000.

mean se_mean sd 10% 90% n_eff Rhat

theta 0.23 0.00 0.09 0.12 0.34 3695 1

lp__ -12.30 0.01 0.71 -13.18 -11.80 3954 1

Samples were drawn using NUTS(diag_e)

For each parameter, n_eff is a crude measure of effective sample size,

and Rhat is the potential scale reduction factor on split chains (at

convergence, Rhat=1).

# Extracting the posterior draws

theta_draws = extract(fit)$theta

# Calculating posterior mean (estimator)

mean(theta_draws)

[1] 0.3207932

# Calculating posterior intervals

quantile(theta_draws, probs=c(0.10, 0.90))

10% 90%

0.1968843 0.4486509

theta_draws_df = data.frame(list(theta = theta_draws))

plotpostre = ggplot(theta_draws_df, aes(x = theta)) +

geom_histogram(bins=20, color = "gray")

plotpostre

RStan: MAP, penalized MLE

Stan's optimization for estimation; two views:

- max posterior mode, also known as max a posteriori (MAP)

- max penalized likelihood (MLE)

library(rstan)

N = 5

y = c(0,1,1,0,0)

model = stan_model(model_code=bern.stan)

mle = optimizing(model, data=c("N", "y"))

print(mle, digits=2)

$par

theta

0.4

$value

[1] -3.4

$return_code

[1] 0

Lotka-Volterra's (1927) Model

Lotka (1925) and Volterra (1926) formulated parametric differential equations that characterize the oscillating populations of predators and preys.

A statistical model to account for measurement error and unexplained variation uses the deterministic solutions to the Lotka-Volterra equations as expected population sizes.

Full Bayesian inference may be used to estimate future (or past) populations.

Stan is used to encode the statistical model and perform full Bayesian inference to solve the inverse problem of inferring parameters from noisy data.

In this example, we want to fit the model to Canadian lynx predator and snowshoe hare prey with repective populations between 1900 and 1920.

Notations and mathematical model

- \( u(t) \) prey,

- \( v(t) \) predator

\[ \frac{d}{dt}u = (\alpha -\beta v)u \]

\[ \frac{d}{dt}v=(-\gamma +\delta u)v \]

- \( \alpha \): prey growth, intrinsic

- \( \beta \): prey shrinkage due to predation

- \( \gamma \): predator shrinkage, intrinsic

- \( \delta \): predator growth from predation

Lotka-Volterra in Stan

real[] dz_dt(data real t, // time

real[] z, // system state

real[] theta, // parameters

data real[] x_r, // real data

data int[] x_i) { // integer data

real u = z[1]; // extract state

real v = z[2];

real alpha = theta[1];

real beta = theta[2];

real gamma = theta[3];

real delta = theta[4];

real du_dt = (alpha - beta * v) * u;

real dv_dt = (-gamma + delta * u) * v;

return { du_dt, dv_dt };

}

Known variables are observed

\( y_{n,k} \): denotes for species \( k \) at times \( t_{n} \) for \( n \in 0:N \)

Unknown variables must be inferred (inverse problem)

initial state: \( z_{k}^{init} \): initial population for \( k \)

subsequent states \( z_{n,k} \): population \( k \) at time \( t_{n} \)

parameters \( \alpha \), \( \beta \), \( \gamma \), \( \delta > 0 \)

Likelihood assumes errors are proportional (not additive)

\[ y_{n,k}\sim LogNormal(\hat{z}_{n,k}, \sigma_{k}), \]

equivalently: \[ \log y_{n,k} = \log \widehat{z}_{n,k} + \epsilon_{n,k} \] with \[ \epsilon_{n,k} \sim Normal(0, \sigma_{k}) \]

Lotka-Volterra in Stan (data, parameters)

- Variables for known constants, observed data

data {

int<lower = 0> N; // num measurements

real ts[N]; // measurement times > 0

real y0[2]; // initial pelts

real<lower=0> y[N,2]; // subsequent pelts

}

- Variables for unknown parameters

parameters {

real<lower=0> theta[4]; // alpha, beta, gamma, delta

real<lower=0> z0[2]; // initial population

real<lower=0> sigma[2]; // scale of prediction error

}

Lotka-Volterra in Stan (priors, likelihood)

Sampling statements for priors and likelihood

model {

// priors

sigma ~ lognormal(0, 0.5);

theta[{1, 3}] ~ normal(1, 0.5);

theta[{2, 4}] ~ normal(0.05, 0.05);

z0[1] ~ lognormal(log(30), 5);

z0[2] ~ lognormal(log(5), 5);

// likelihood (lognormal)

for (k in 1:2) {

y0[k] ~ lognormal(log(z0[k]), sigma[k]);

y[ , k] ~ lognormal(log(z[, k]), sigma[k]);

}

}

Lotka-Volterra in Stan (solution to ODE)

We have to define variables for populations predicted by

ode, given:System function (

dz_dt), initial populations (z0).initial time (

0.0), solution times (ts).parameters (

theta), data arrays.tolerances (

1e-6, 1-e4), max iterations (1e3).

transformed parameters {

real z[N, 2]

= integrate_ode_rk45(dz_dt, z0, 0.0, ts, theta,

rep_array(0.0, 0), rep_array(0, 0),

1e-6, 1e-4, 1e3);

}

Lotka-Volterra Parameter Estimates

fit = stan(model_code=lotka-volterra.stan, data = lynx_hare_data)

print(fit, c("theta", "sigma"), probs=c(0.1, 0.5, 0.9))

mean se_mean sd 10% 50% 90% n_eff Rhat

theta[1] 0.55 0 0.07 0.46 0.54 0.64 1168 1

theta[2] 0.03 0 0.00 0.02 0.03 0.03 1305 1

theta[3] 0.80 0 0.10 0.68 0.80 0.94 1117 1

theta[4] 0.02 0 0.00 0.02 0.02 0.03 1230 1

sigma[1] 0.29 0 0.05 0.23 0.28 0.36 2673 1

sigma[2] 0.29 0 0.06 0.23 0.29 0.37 2821 1

Obtained Results

Rhat near 1 signals convergence; n_eff is effective sample size

10%, … posterior quantiles; e.g., \( P[\alpha \in (0.46,0.64)|y]=0.8 \)

posterior mean is Bayesian point estimate: \( \alpha = 0.55 \)

standard error in posterior mean estimate is 0 (with rounding)

posterior standard deviation of \( \alpha \) estimated as 0.07

Other references and examples of Stan

- Andrew Gelman's blog about Rstan in RStudio Cloud

https://andrewgelman.com/2018/10/12/stan-on-the-web-for-free-thanks-to-rstudio

- Examples Session in RStudio Cloud

https://rstudio.cloud/project/56157

But I had problems to run these codes in the Cloud: RStudio in Cloud is version alpha :-(

Anyway, all examples of his blog can be donloaded from

https://github.com/stan-dev/example-models/archive/master.zip

Development Team of STAN

Andrew Gelman, Bob Carpenter, Daniel Lee, Ben Goodrich, Michael Betancourt, Marcus Brubaker, Jiqiang Guo, Allen Riddell, Marco Inacio, Jeffrey Arnold, Mitzi Morris, Rob Trangucci, Rob Goedman, Brian Lau, Jonah Sol Gabry, Robert L. Grant, Krzysztof Sakrejda, Aki Vehtari, Rayleigh Lei, Sebastian Weber, Charles Margossian, Vincent Picaud, Imad Ali, Sean Talts, Ben Bales, Ari Hartikainen, Matthijs Vakar, Andrew Johnson, Dan Simpson