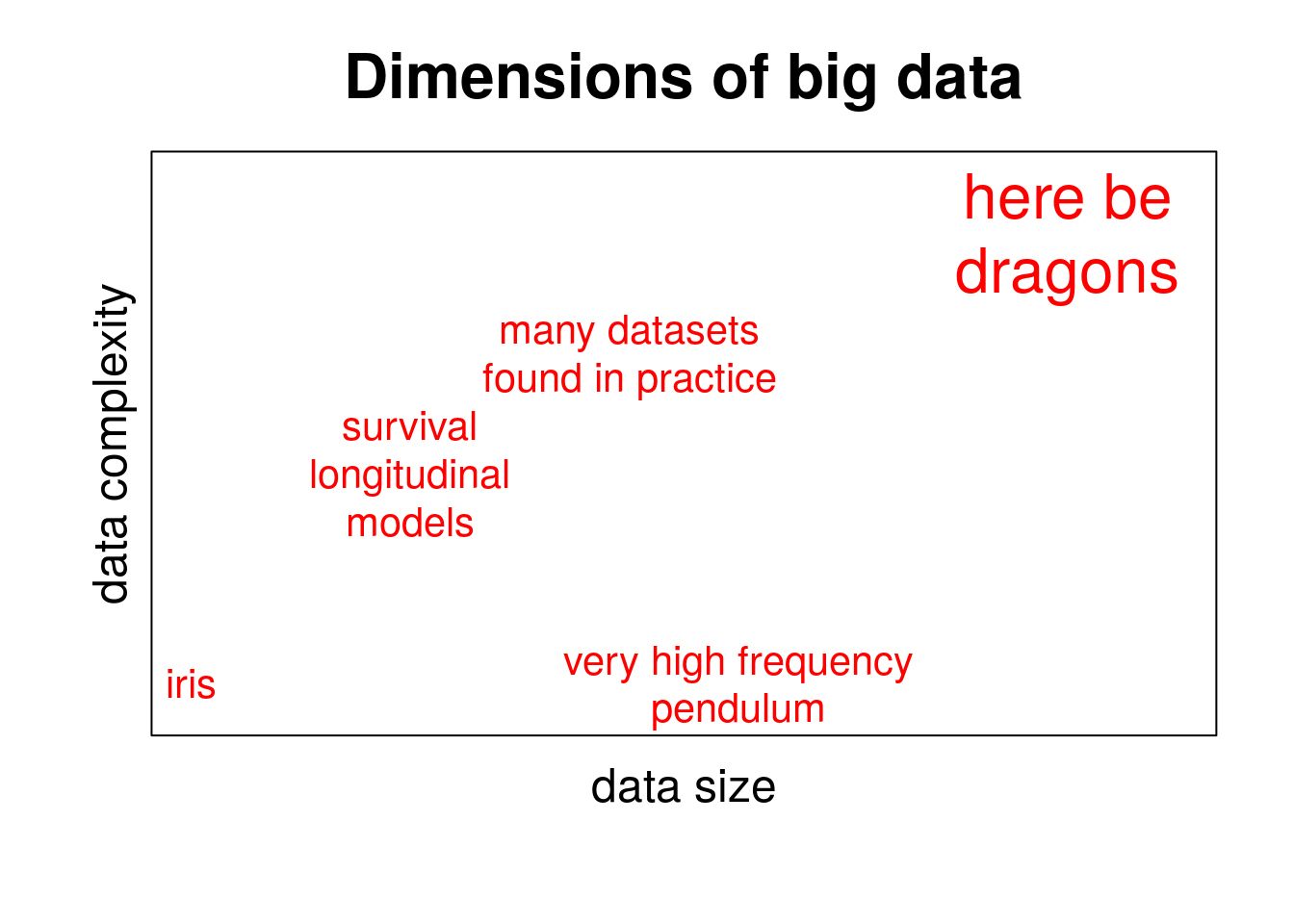

Big datasets found in statistical practice often have a rich structure. Most traditional methods, including their modern counterparts, fail to efficiently use the information contained in them. Here we propose and discuss an alternative modelling strategy based on herds of simple models.

Big Data: How big datasets came to be

Data has not always been big. Classical datasets such as the famous Anderson’s iris dataset, were often small. Many of the best known statistical methods do also deal with the problems posed by data scarcity rather than data abundance. The paramount example is the ubiquitous Student’s t-test, which explores a simple dichotomous dependency for otherwise homogeneous data providing so few degrees of freedom that the normal approximation to the underlying t distribution is still too problematic.

Big data did not just spring up all of a sudden and out of nothing. Datasets grew and we saw them growing until, at some point, we were told that we had entered the Big Data era. Die hard Marxists would say that a quantitative change brought along a qualitative change.

But not all datasets grew in the same way: some growth patterns were more interesting than others. Very naively, one could say that datasets grew because they earned either more rows or more columns. Certainly, you can make a dataset grow in both directions without making it more interesting or, arguably, more informative. Often, datasets have a very flat structure and they do not become particularly richer by gaining extra rows of columns. One can think in examples such as simple mechanical systems (e.g., a pendulum): increasing the time resolution of the measures does not result in extra information about the system beyond certain frequency (see Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem). Similarly, knowing the temperature at meteorological stations every minute, second or, perhaps, millisecond would increase the volume of the data they generate, but extra rows would become a nuisance in most if not all applications. Likewise, adding an extra temperature sensor in a monitored system whose measurements would strongly correlate with every other temperature sensor would certainly add a new column to the dataset but we know users would just summarize all these measurements using PCA or a similar technique.

The size dimension of big data is little more than a nuisance when data structure is flat. Size is key, however, when it reveals additional layers of structure. In fact, many of the datasets of interest nowadays are highly structured. These will be discussed in the following section.

However, I need to remark here that I did not attempt to create a complete taxonomy of data growth mechanisms (these supposedly being flat growth in the number of rows and/or columns vs hierarchical or structured growth).

Hierarchical datasets

Many datasets of interest in my consulting practice are hierarchical. Not only they have a very obvious hierarchical structure, but we can also trace their historical growth process.

Take banks. I had a project at BBVA when they celebrated their 150 anniversary. I performed the mental exercise of imagining what kind of datasets would the bank manage at that time. They were probably terse and simple data summaries with aggregated data at regional level with monthly or quarterly periodicity. At some time they would have been able to include and process product level information at branch level and only quite recently to add the customer as the main data subject. Nowadays, information pertaining to each customer and including his products and their timestamped transactions will probably make a richer dataset than the whole bank managed in their early days. Information in this case grew by branching, i.e., by acquiring a hierarchical structure where branches have customers who own products and make transactions with them over time.

Another example from my consulting experience: a few years ago I was given a medical dataset to study some patterns in patients of diabetes. It came from a local hospital and it contained a few hundred rows, each concerning a different patient. And no matter what I tried, I consistently came across the same recurring outlier. I finally had a close look at that patient and found out that as well as diabetes, he was suffering from a number of other acute illnesses, AIDS being one of them. I finally discarded such case, but I always thought that in a wider analysis deserving the Big Data stamp, he together with other similar patients would have made a very interesting subdataset to study.

Hierarchical datasets as those discussed above but, of course not limited to them, are common in the daily practice of statistical consulting. However, they are still being studied using the old Anderson iris dataset tradition, using unjustifiable iid (independent, identically distributed) assumptions on data rows and either classical statistical methods or their modern —more able but still pertaining to the same tradition— data science counterparts, including XGBoost and the like.

Statistical analysis of hierarchical datasets

The main idea in the analysis of hierarchical datasets is embodied in the following formula:

\[M = \alpha(I_i) M_i + (1 - \alpha(I_i)) M_g\]

\(M\) above is our final model. It consists of two parts: an individual model, \(M_i\), specific for each subject \(i\), and a global model \(M_g\) that applies to all subjects and acts like a default or a priori model. The final models \(M\) is closer to either \(M_i\) or \(M_g\) depending on the amount of information, \(I_i\), available about subject \(i\).

It should be noted that the formula above needs not be taken literally. In particular, the convex combination between models \(M_i\) and \(M_g\) does not literally mean weighted mean. Also, these models need not be explicitly constructed. Therefore, the expression above should be taken as a guiding principle which may adopt (and, in practice, does adopt) many different forms that I’ll discuss in what follows.

Sample data

In order to illustrate the principles above, I am going to construct some sample data. It resembles data from two of our last projects, and I have attempted to preserve most of their structure in the smallest possible number of rows and columns.

The data setup is as follows: a number of users belonging to two groups like or dislike items belonging to three different categories.

ns <- 9 # number of subjets

ng <- 2 # number of subject groups

nc <- 3 # number of categories

subjects <- factor(1:ns)

groups <- factor(1:ng)

categories <- factor(1:nc)Users belong to groups (assigned at random) and they have been exposed to an unequal number of items. In fact, in practice, it is very common to have very unbalanced datasets, combining subjects with a solid history record together to newcomers from whom very little is known.

subject_group <- data.frame(subject = subjects,

group = sample(groups, length(subjects), replace = T),

n_items = 10 * 1:length(subjects))

dat <- ldply(1:nrow(subject_group), function(i){

tmp <- subject_group[i,]

res <- merge(tmp, data.frame(category = sample(categories, tmp$n_items, replace = T)))

res$n_items <- NULL

res

})Here we construct the target variable, y, indicating whether or not a subject liked certain item. That he likes it depends on the group the subject belongs to (weak effect), the category of the item (stronger effect) and, finally, the item itself (intermediate effect).

Note: Here, for the sake of presentation, we are ignoring the item ids. In fact, item ids would be relevant in applications such as recommendation systems this artificial data may have some resemblance to. Another feature this dataset ignores is the time dimension. Interactions happened at some point in time and oldish interactions could be sensibly weighted down in actual applications.

sigma_ct <- .5

cat_type <- expand.grid(group = groups, category = categories)

cat_type$ct_coef <- rnorm(nrow(cat_type), 0, sigma_ct)

sigma_cs <- 1.5

cat_subj <- expand.grid(subject = subjects, category = categories)

cat_subj$cs_coef <- rnorm(nrow(cat_subj), 0, sigma_cs)

sigma_item <- 1

dat <- merge(dat, cat_type)

dat <- merge(dat, cat_subj)

dat$item_coef <- rnorm(nrow(dat), 0, sigma_item)

dat$y <- with(dat, exp(ct_coef + cs_coef + item_coef))

dat$y <- dat$y / (1 + dat$y)

dat$y <- sapply(dat$y, function(p) rbinom(1, 1, p))

dat$ct_coef <- dat$cs_coef <- dat$item_coef <- NULL

knitr::kable(head(dat), "html")| category | subject | group | y |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

Typical modelling strategy

The most typical modelling strategy found in practice to model this kind of data is based on the formula

f0 <- y ~ category + groupor perhaps

f1 <- y ~ category * groupThese formulas can be embedded in many different fitting functions, glm being a baseline. Today data scientists would prefer modern alternatives to traditional glm, such as glmnet, random forests, or different versions of boosting. It should be noted —and it will be discussed below— how little advantage (other than regularization when available) these modern methods provide with respect to the baseline in the analysis of structured datasets.

model_00 <- glm(f1, family = binomial, data = dat)

summary(model_00)##

## Call:

## glm(formula = f1, family = binomial, data = dat)

##

## Deviance Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -1.5409 -1.0691 -0.6835 1.0471 1.7712

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -0.2603 0.2188 -1.190 0.234142

## category2 -1.0747 0.3332 -3.226 0.001258 **

## category3 0.5748 0.2924 1.966 0.049297 *

## group2 0.1268 0.3703 0.342 0.732152

## category2:group2 2.0314 0.5294 3.837 0.000124 ***

## category3:group2 -0.8766 0.4996 -1.754 0.079354 .

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 619.91 on 449 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 572.91 on 444 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 584.91

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4Exercise: compare the coefficients obtained above with those contained in table

cat_type.

In general, this approach does approximate group preferences well. But group preferences (or fixed effects) do not tell the whole story about individual behaviour. Fixed effects are of interest in academic environments (e.g., statements of the form men in such age group tend to…) but are often of limited interest in practice, where accurate predictions of individual behaviour are needed.

Going back to

\[M = \alpha(I_i) M_i + (1 - \alpha(I_i)) M_g,\]

using the approach above is tantamount to taking \(M = M_g\).

However, this is standard practice in many applied fields and the problem is often mitigated by creating thinner user categorizations —or microsegmentations—, i.e., increasing the number of fixed factors and, therefore, increasing the number of rows in the datasets.

Adding users

One can try to add users to the model above. For example, doing something not unlike this:

f_users <- y ~ category * group + category * subject

model_01 <- glm(f_users, family = binomial, data = dat)

summary(model_01)##

## Call:

## glm(formula = f_users, family = binomial, data = dat)

##

## Deviance Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -2.1219 -0.8305 -0.4673 0.8712 2.1301

##

## Coefficients: (4 not defined because of singularities)

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -0.8473 0.4880 -1.736 0.08249 .

## category2 -1.2730 0.7819 -1.628 0.10353

## category3 -0.1888 0.6011 -0.314 0.75344

## group2 -16.1881 2797.4420 -0.006 0.99538

## subject2 34.6015 3426.1527 0.010 0.99194

## subject3 15.5314 2797.4421 0.006 0.99557

## subject4 17.5054 2797.4421 0.006 0.99501

## subject5 2.7191 0.9028 3.012 0.00260 **

## subject6 16.6788 2797.4420 0.006 0.99524

## subject7 0.6931 0.6268 1.106 0.26878

## subject8 -0.2513 0.6785 -0.370 0.71107

## subject9 NA NA NA NA

## category2:group2 35.8745 3127.6353 0.011 0.99085

## category3:group2 -0.3418 0.8977 -0.381 0.70335

## category2:subject2 -51.8799 3700.6680 -0.014 0.98881

## category3:subject2 -17.2586 1978.0904 -0.009 0.99304

## category2:subject3 -15.5314 3394.2809 -0.005 0.99635

## category3:subject3 3.4210 1.2964 2.639 0.00832 **

## category2:subject4 -35.3228 3127.6353 -0.011 0.99099

## category3:subject4 -0.9202 1.1081 -0.830 0.40629

## category2:subject5 -1.6974 1.2336 -1.376 0.16881

## category3:subject5 0.4571 1.2235 0.374 0.70873

## category2:subject6 -33.4716 3127.6352 -0.011 0.99146

## category3:subject6 NA NA NA NA

## category2:subject7 1.1648 0.9711 1.199 0.23039

## category3:subject7 0.8285 0.8473 0.978 0.32821

## category2:subject8 0.2121 1.0979 0.193 0.84682

## category3:subject8 2.7690 0.9105 3.041 0.00236 **

## category2:subject9 NA NA NA NA

## category3:subject9 NA NA NA NA

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 619.91 on 449 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 472.04 on 424 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 524.04

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 16This is not practical with realistic datasets for a number of reasons. The most important one is related to the large number of coefficients that need to be fitted and the huge amount of memory required to fit the models. Note that whereas the number of columns is relatively limited, the internal objects required to perform the fit are huge and grow linearly with the number of subjects:

dim(model.matrix(model_01))## [1] 450 30Moreover, tools intended to reduce the number of dimensions (read: lasso) would effectively eliminate information about certain subjects, and this is precisely contrary to our purpose.

Finally, you would face cold start problems in full bitterness. There may be little information about certain new subjects and the model would completely fail to associate a reasonable prediction to them. With zero observations, the model would be clueless about subject preferences and with a single observation, the model would seem overconfident on them (the 100% paradox!)

Therefore, some degree of regularization, the kind of regularization that ridge regression promises, could be of some help, but it would also fail in largish models.

Ideal modelling strategy

The ideal modelling strategy is also hugely impractical for large datasets: the full Bayesian route. In this case I will use the stanarm wrapper rather than creating stan program. However, in more general problems not covered by stanarm one would still have to model the problem using ad hoc code.

model_stan <- stan_glm(f_users,

data = dat,

family = binomial(link = "logit"),

prior = student_t(df = 7),

prior_intercept = student_t(df = 7),

cores = 2, seed = 12345)

model_stan## stan_glm

## family: binomial [logit]

## formula: y ~ category * group + category * subject

## observations: 450

## predictors: 30

## ------

## Median MAD_SD

## (Intercept) 0.0 1.2

## category2 -0.6 1.1

## category3 0.4 1.1

## group2 0.5 1.3

## subject2 1.3 1.3

## subject3 -1.4 1.1

## subject4 0.0 1.0

## subject5 1.8 1.3

## subject6 -0.8 1.0

## subject7 -0.1 1.2

## subject8 -1.0 1.2

## subject9 -0.9 1.2

## category2:group2 2.5 1.4

## category3:group2 -1.6 1.4

## category2:subject2 -3.1 1.6

## category3:subject2 -0.7 1.4

## category2:subject3 3.0 1.9

## category3:subject3 3.5 1.4

## category2:subject4 -2.5 1.3

## category3:subject4 -0.2 1.2

## category2:subject5 -2.2 1.3

## category3:subject5 0.2 1.4

## category2:subject6 -0.8 1.2

## category3:subject6 0.6 1.2

## category2:subject7 0.4 1.2

## category3:subject7 0.3 1.1

## category2:subject8 -0.6 1.3

## category3:subject8 2.1 1.2

## category2:subject9 -0.7 1.3

## category3:subject9 -0.5 1.1

##

## ------

## * For help interpreting the printed output see ?print.stanreg

## * For info on the priors used see ?prior_summary.stanregThis is the best thinkable modelling approach in all dimensions but one: it’s completely unfeasible on largish data. In fact, it is an active area of research (see Bayes and Big Data: The Consensus Monte Carlo Algorithm for instance). It fully implements our

\[M = \alpha(I_i) M_i + (1 - \alpha(I_i)) M_g\]

plan, but we’ll have to wait a couple of generations before Moore’s Law does its job and we can run these models on laptops.

Naive herds of models

One naive (but still useful) approach to modelling data like the one discussed above is to build one model per subject (say, glm). Again, this would mean using \(M = M_i\). In such case, it would not be necessary to use the group variable, as users already belong to one such group (and in practical terms, we would face colinearity issues). For instance, one could build a model as follows:

f_ind <- y ~ category

my_models <- dlply(dat, .(subject), function(tmp){

glm(f_ind, family = binomial, data = tmp)

})Models like these are rare but not unheard of in applications. Since every subject becomes a dataset, it is possible to create models using information contained in their dataset only and identify \(M = M_i\).

Models become simpler, but they also raise engineering issues: we need to build our own unorthodox scoring/prediction functions. But at a deeper level, they raise a number of additional and very interesting (often research-grade) questions:

- How do we measure goodness of fit?

- How do we know the model is not behaving oddly?

- How do we deal with subjects with little history/data?

We can improve upon these naive herds of models where \(M = M_i\) by turning our interest to the \(M_g\) part of the naive models just discussed discard.

More advanced herds of models

I will indicate here three strategies to improve the naive herds of models. They are all related to the reintroduction of the \(M_g\) term in the herd. The first improvement consists in using regularized versions of the glm function above. In practice, I have found the package lme4 very useful for these purposes.

my_models <- dlply(dat, .(subject), function(tmp){

glmer(y ~ (1 | category), family = binomial, data = tmp)

})However, we are not yet using the hierarchical structure of the dataset. Regularization like above help avoid the 100% problem (among others), but fails to exploit the possible relationships among subjects. In fact, in our example and in most real-life datasets, part of the strength of the relationship between subjects and categories can be explained precisely because subjects belong to groups. These groups embody all we know about individuals without having seen them behaving.

And, of course, the relationship between the target variable and the group can be estimated before and independently of the estimation of the relationship between this user and the target variable. Then, those group relationships need to be inserted into the model, usually, via informative priors.

Note: I’m still searching for a good, efficient method that will let me include informative priors in subject models.

Note: academia is interested in fixed effects. Consulting practice is mostly concerned with random effects (what individuals do). Academia’s input to consulting job is precisely providing good priors. That’s in part why we pay taxes.

Alternatively, we could generate models in wider batches. Not only because of efficiency, but also to facilitate the inclusion of priori information in the final model. For instance, one could attempt the following:

my_models <- dlply(dat, .(group), function(tmp){

glmer(y ~ (1 + category | subject), family = binomial, data = tmp)

})## boundary (singular) fit: see ?isSingularHere we are splitting the data according to the group, so the prior information contained that all members of a group share is again fully used. Still, it could be the case that the group split produced too large parts for glmer to process them. Another option would be to subsplit groups in pieces large enough to have a relative accuarate description of the prioristic parts but small enough to process them efficiently.

As an alternative, for some kind of models, INLA could provide a handy replacement to lme4::glmer.

Note: I did some very promising tests of INLA in a recent project where performance was a must (and our datasets contained users in the order of 1 million), but it did not finally make it to the final deliverable.

Areas of future improvement

The discussion above opened a number of questions, many of them are open to researchers in statistics and computer science:

- How to fit full Bayesian models with big data efficiently. In particular, how to fit them by pieces and how to combine them.

- How to efficiently feed a priori information on individual (per subject) models.

- How to assess the goodness of fit of herds of models; particularly of herds consisting of a large number of models, often in the range of millions.

Summary

- Many large datasets found in consulting practice have a clear hierarchical structure.

- Standard data science models often fail to use such structure efficiently.

- Although Bayesian approaches are more promising, they are mostly unusable nowadays given the lack of computing power required to run them at full scale.

- However, it is possible to fit herds of models to reduce to the minimum expression the amount of information loss in the modelling process.

- But building these herds of models requires an intelligent design in order to both attain reasonable computing efficiency and to adequately use as much a priori information as possible.